From Fear to Action: Understanding and Coping with Climate Anxiety

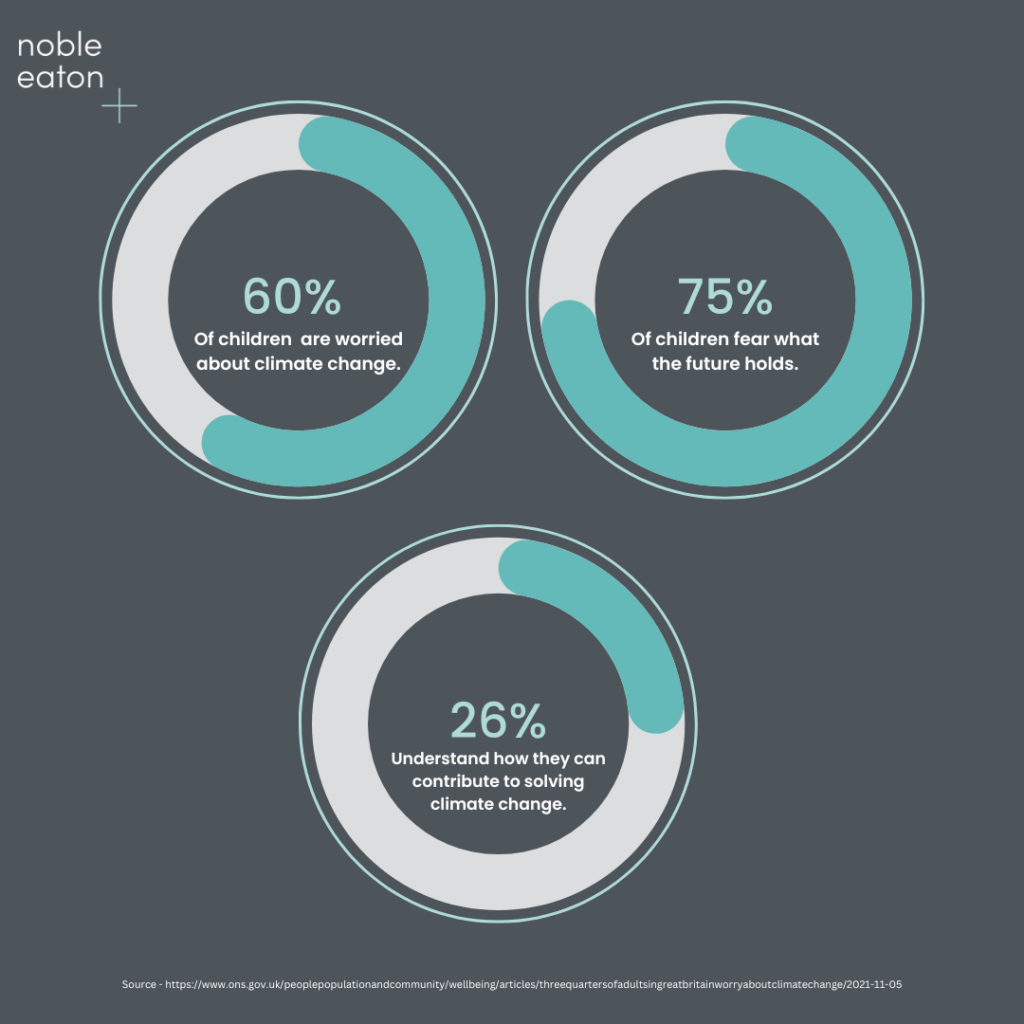

The pressing issue of climate change looms over us like a dark cloud. Approximately, 60% of children are worried about climate change, with a staggering 75% fearful for the future. Despite living in an age of abundant information, many students find themselves paralysed by uncertainty, suffering from eco-anxiety. However, by understanding the cognitive and psychological mechanisms behind this anxiety, we can turn that fear into action and turn into a powerful force for positive change.

What is eco-anxiety?

Starting from the top: what does eco-anxiety mean exactly? In its simplest form, eco-anxiety is the chronic fear of environmental doom, ranging from stress to clinical disorders such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide [2]. Whilst this is an issue that all ages can struggle with, it’s particularly present among children and young people [1,2].

As it stands, eco-anxiety is not an officially diagnosed condition, owning various labels that may contribute to the confusion, such as solastalgia, climate grief, environmental despair, eco-guilt, and so on [3]. Regardless of the name, there is rising interest in the topic [4], but the research itself is ongoing. More data is required, allowing the opportunity for further theoretical discussion. Yet, it is not unapproachable.

Where does eco-anxiety stem from?

We’ve mentioned some ways eco-anxiety can rear its head, but it’s crucial to understand where it comes from. There are many potential factors, such as the depletion of nature itself, the rise of exacerbated and atypical natural disasters, and the ominous, seemingly hopeless warnings that mainstream media channels run in a cyclical nature.

In fact, research has found that a worrying number of environmental educators are experiencing serious mental health conditions due to the relentless exposure to environmental damage and the overwhelming pressure to take action [5]. Overall, dialogue surrounding the climate change seems to lean heavily towards the ‘doom’ end of the spectrum, regardless of any innovations or technological advancements that offer hope. However, hope is undoubtedly part of the conversation [6].

The Window of Tolerance

We must look internally to understand and the address the roots of such emotions. How we respond to the climate crisis can be viewed through the Window of Tolerance [7]. Coined by clinical professor of psychiatry Daniel J. Siegel, The Window of Tolerance presents the optimal emotional ‘zone’ we can reside in, allowing us to thrive and function throughout our daily life.

Bracketing the ‘optimal zone’ are two separate zones: the hyper-arousal zone and the hypo-arousal zone. The optimal zone (the Window of Tolerance) is distinguished by a sense of curiosity, presence, flexibility, emotional regulation, and the ability to weather life’s potential stressors [7].

Why is this significant? People who frequently operate outside their Window of Tolerance are prone to experiencing mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. When this window, or optimal zone, has been eclipsed, they may have a chaotic (hyper-arousal) or stunned (hypo-arousal) response, including helplessness, anger, and panic, or denial and numbness.

The proposed solution here? Truthfully, it would be impossible for our optimal zones avoid being obscured. However, there are ways to bolster our resilience, recognise our internal workings, and increase our Window of Tolerance to deal with issues such as eco-anxiety.

Eco-anxiety: tackling it from the inside out

Firstly, it’s vital for young people to realise that the Window of Tolerance is subjective. Everyone has different histories, resulting in differing traumas and responses. No two optimal zones will look the same. Therefore, it’s important to familiarise oneself with their Window of Tolerance.

Once someone is more in tune with it, the more likely they’ll be able to take actional steps [8]. If the optimal zone is shrouded, how we react is crucial. As climate activist Clove Hogan says:

your mindset is the only thing you can control and it’s your greatest power to deal with climate change and eco anxiety.

Whilst each of us will react in a different way, it’s beneficial that we recognise our anxiety. Whereby the opportunity to generate a tailored response presents itself. Particularly for the younger generation it can be hard to understand that what we label as ‘bad’ emotions, such as guilt and shame, are inevitable.

Research supports this, as seen through Jensen’s [10] innovative monograph, which explores the prevalence of guilt in conversations or behaviours centred around environmental issues. This study is particularly impactful due to its ability to transcend beyond black-and-white interpretations of particular emotions, providing what we may perceive to be ‘negative’ emotions with other dimensions [11, 12, 13]. Essentially, the greater our awareness of our internal processing, the simpler it will be to understand and regulate such emotions.

The tangible consequences of eco-anxiety

Now, this can all seem a little abstract, particularly due to the limited research focused on eco-anxiety. However, statistics [14] are a clear way to gauge this issue on a macro scale:

- In October 2021, three-quarters (75%) of adults in Great Britain said they were either very or somewhat worried about the impact of climate change, while around one-fifth (19%) were neither worried nor unworried.

- Around 8 in 10 women (79%) reported being either very or somewhat worried. This was statistically significantly higher than the proportion of men reporting this (72%)

- Only 26% of participants agreed that they ‘feel like I have a clear idea of how I can contribute to solving climate change’.

A global online survey carried out in 2021 is also a good indicator, carried out by Caroline Hickman, a psychotherapist at the University of Bath. It collected data from 10,000 teenagers and young adults aged 16-25 in 10 countries, including the UK, US, Brazil, India and the Philippines. Close to 60% of participants said they felt ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ worried about climate change, while 75% said ‘the future is frightening’ [1]. From these numbers, it’s arguable that eco-anxiety is an insidious presence that holds the potential to disrupt many young people’s well-being.

Coping with eco-anxiety

It’s clear that educators play a crucial role in creating an environment that eases potential eco-anxiety. Many young people have the ability to discover facts about issues such as climate change autonomously, yet it may be challenging to regulate and process such information. Educators have another responsibility here: to be aware of consistent patterns that arise when teaching students about climate issues. Renee Lertzman, climate psychologist and founder of Project InsideOut [19], discovered a series of trends. Lertzman found that students experienced what she calls the ‘3 A’s’: anxiety, ambivalence, and aspiration. Let’s break these down.

Anxiety – calling back to the Window of Tolerance; this involves students trying to process large, complex problems while also dealing with complicated and contradictory emotions. Understanding anxiety and recognising how it impacts our capacities to engage with these complex issues, is fundamental when managing these emotions. The ability to comprehend one’s own anxiety can result in a change of mindset in the face of challenges and solutions.

Ambivalence – when faced with an overload of stimuli, it’s common for young people to question the natural conflicts and dilemmas that they encounter when faced with such an imposing reality. This can lead to a call for radical change. Essentially, ambivalence is a key ingredient in how people process new solutions and engage collectively with looming global issues.

Aspirations – despite the lingering threat of climate change, it’s natural for younger people to aspire towards a safe, healthy future. Hope is a key element that drives us as a species. In the face of eco-anxiety, it’s a consistent trend that allows conflicting emotions to experience a sense of equilibrium.

Once these patterns are recognised, meaningful leadership can be ta Lertzman believes people care about these issues, yet previous leadership experiences have not allowed us to engage with people respectfully. Her research suggests that if people are heard, understood, and included in an authentic way, we can collaboratively reach our goals. To successfully achieve this, educational leaders must establish a ‘new mindset and skill set as leaders’ [20].

Anxiety and the brain

In the words of Lertzman: ‘To change the trajectory of the world, we must first change the way we lead’. Without a deeper understanding of anxiety, educators will find themselves with a tall order. We can recognise trends, yet transforming the delivery of the message is imperative if we want to achieve meaningful change.

So, let’s strip everything back and observe the effect anxiety has on the brain.

When anxiety is triggered, our amygdala activates, seizing our thought processes and diminishing our ability to access the prefrontal cortex. Our prefrontal cortex allows us to access strategy, foresight, empathy, and nuanced thinking. Each one of these attributes is extremely important when attempting to understand and cope with ecological issues. [21]

The impact of a positive mindset

For environmental threats, many psychologists studying anxiety have discovered how it triggers a range of defence mechanisms, causing us to avoid, rationalise, minimise, discount, deny, dissociate, and project away from this uncomfortable reality. The mere mention of climate change, even in a positive light, can cause these emotional reactions. This coincides with a lack of control. Therefore, it’s vital to recognise elements that are in our control, including our mindset.

To veer away from the insipid mantra of ‘just have a positive mindset and everything will be okay’, it’s beneficial to explore our mindset through the lens of psychologist Carol Dweck in the form of ‘fixed’ and ‘growth’ [22].

- Fixed mindset: this is characterised by the belief that one’s intelligence, abilities, and talents are fixed traits that cannot be changed. People with a fixed mindset often believe that these inherent traits determine their success or failure and that there is little they can do to change the outcome. They may avoid challenges and give up easily, believing that effort is not worth it if they don’t have the natural ability to succeed.

- Growth mindset: this is the belief that one’s intelligence, abilities, and talents can be developed through hard work, dedication, and perseverance. People with a growth mindset see challenges as opportunities for growth and learning and believe that effort is a key ingredient for success. They are more likely to embrace challenges, persist through difficulties, and view failures as opportunities for learning and improvement.

Recognising this is important, as research has shown that the fixed mindset of anxiety – the belief that anxiety is rigid and immovable – is closely aligned with a number of psychological distress symptoms and approaches toward emotional regulation. A recent study [23] found that the fixed mindset of anxiety is predictive of distress over the future, regardless of previous remedies. As such, finding methods to instil a positive mindset is integral, particularly for younger people who require guidance in regulating their emotions.

Change requires awareness

Ultimately, there’s no denying that it’s an uncertain time to be a young person. The spotlight is brighter than ever upon the future of our environment, and this spotlight has made us painfully aware of the possible consequences of our actions. However, it’s essential to fight awareness with awareness.

Awareness of our internal processing, of our relationship with eco-anxiety – and anxiety in general.

Awareness of ways we can equip educators with the right tools to support their students, guiding them to a sense of understanding. With the right approaches, it’s entirely possible to convert fear into action.

References

[1] Marks, E. et al. (2021) “Young People’s Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon,” Social Science Research Network [Preprint].

[2] Dodds, J. (2021) “The psychology of climate anxiety,” BJPsych Bulletin, 45(4), pp. 222–226.

[3] Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836.

[4] Climate anxiety or climate distress? Coping with the pain of the climate emergency (2019).

[5] Fraser, J.F. et al. (2013) “Sustaining the Conservationist,” Ecopsychology, 5(2), pp. 70–79.

[6] Russell, C. (2016) Editorial: Engaging the Emotional Dimensions of Environmental Education.

[7] Corrigan, F., Fisher, J. and Nutt, D.J. (2011) “Autonomic dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma,” Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(1), pp. 17–25.

[8] Buczynski, R., PhD (2022) How to Help Your Clients Understand Their Window of Tolerance.

[9] Owen-Burge, C. (2023) Clover Hogan: We’re not going to solve the climate crisis with the same thinking that created it – Climate Champions.

[10] Jensen, T.K. (2019) Ecologies of Guilt in Environmental Rhetorics, Springer eBooks.

[11] Climate anxiety (2021).

[12] Is Shame Necessary?

[13] Climate Crisis, Psychoanalysis, and Radical Ethics (no date).

[14]“Three-quarters of adults in Great Britain worry about climate change – Office for National Statistics” (2021) www.ons.gov.uk [Preprint].

[15] Ojala, M. (2007) Hope and worry : exploring young people’s values, emotions, and behavior regarding global environmental problems.

[16] Ojala, M. (2005) “Adolescents’ Worries about Environmental Risks: Subjective Well-being, Values, and Existential Dimensions,” Journal of Youth Studies, 8(3), pp. 331–347.

[18] Ojala, M. (2015) “Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations With Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation,” The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(3), pp. 133–148.

[19] LaraKroeker (2020) Project InsideOut – PIO.

[20] Renée Lertzman (2022).

[21] LaraKroeker (2020a) Anxiety – PIO.

[22] biglifejournal.com Fixed Mindset vs. Growth Mindset Examples.

[23] Schroder, H.S. et al. (2019) “The Fixed Mindset of Anxiety Predicts Future Distress: A Longitudinal Study,” Behavior Therapy, 50(4), pp. 710–717.

Leave a Reply