Wired for Sound: How Acoustics impact Connectedness in School

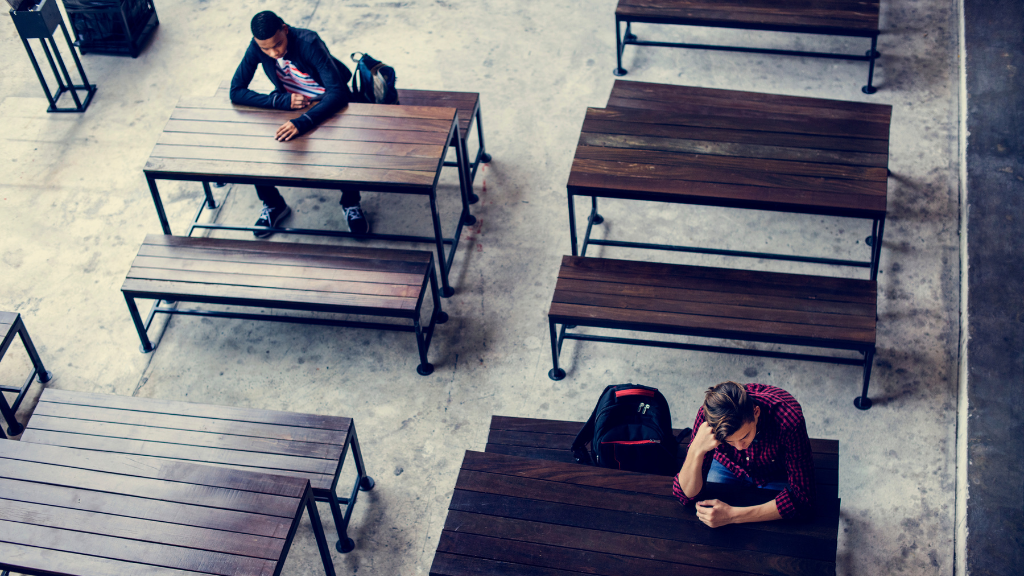

At some stage in our lives, we all feel lonely. For young people, who are still acquiring social skills and navigating the obstacles of adolescence, coping with loneliness can be particularly difficult. As children often find themselves surrounded by people – be it their peers, teachers, or family – it’s forgivable to be unaware of this epidemic.

However, eye-opening statistics from the UK Office on National Statistics (ONS) on loneliness have shone a disconcerting light on the issue, revealing that the loneliest group fell with those aged 16-24 years [1]. In addition, a considerable proportion of children, precisely 11% of those aged 10-15 years and 14% of those aged 10-12 years, expressed frequent feelings of loneliness.

As a multipronged issue, such statistics leave us with a pressing question: why are young people experiencing isolation? From their external environment to their internal build-up, the causes are plentiful and prevalent. However, before we seek an answer, it’s essential to strip the matter down to its foundation, starting with the science behind pre-adolescent and adolescent minds.

The Adolescent Brain and Loneliness

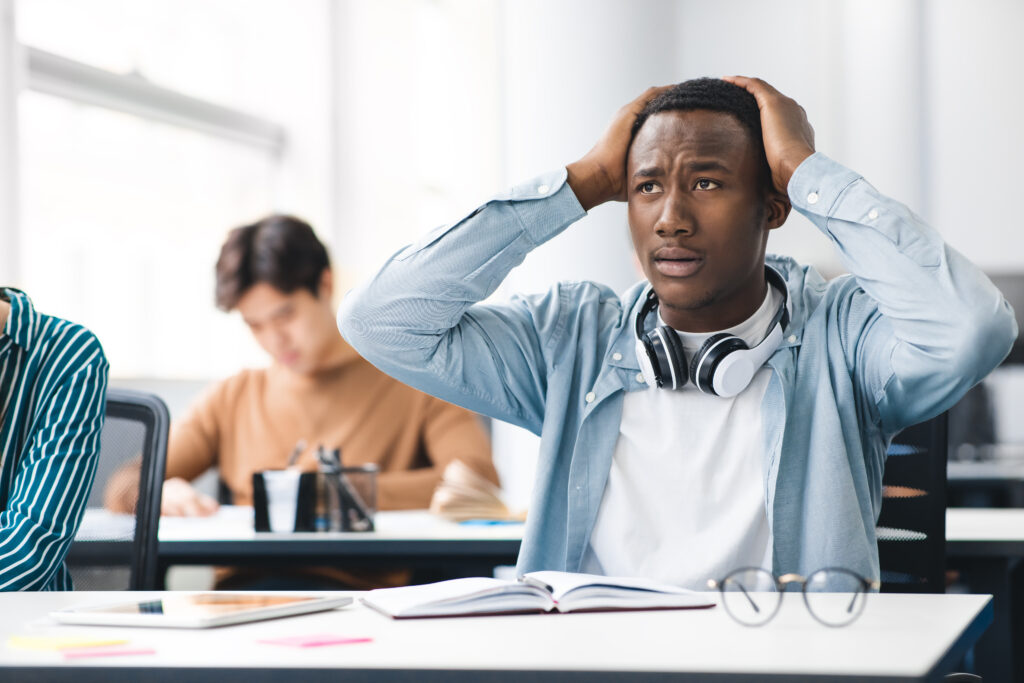

Formative periods are taxing for anyone. But what if we had to experience formative periods in the midst of a volatile storm? This is exactly what the teenage brain undergoes. Partly due to hormonal fluctuations, the adolescent brain creates new synapses and trims away unnecessary ones, essentially honing overall functions [2]. However, Deanna Barch, chair and professor of psychological and brain sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, explains how this transformative process can allow ‘a lot of vulnerability for things to go wrong’ [3].

With this in mind, we need to consider the potential triggers accelerating loneliness in young people. As the adolescent brain is more likely to be vulnerable during a chaotic, transitional time, we must be aware of environmental factors that could contribute to feelings of detachment. It’s pivotal that schools are designed to remedy this. .

Feeling the Consequences of the Pandemic

In the wake of the pandemic, society is still feeling the reverberations of its impact. Worryingly, a recent study showed that teen brains aged faster than normal due to the stress of lockdowns [4]. Published in Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science [5], the study compared scans of the physical structure of teenagers’ brains pre and post-lockdown.

Through the examination of MRI scans from 128 children, with half taken before and the other half after the initial year of the pandemic, the scientists discovered an increase in the size of the hippocampus and amygdala, regions of the brain that are responsible for managing memory retrieval and facilitating the regulation of emotions such as fear and stress. They also found thinning of the tissues in the cortex. While these changes occur during typical adolescent development, the pandemic appeared to have accelerated the process.

The Rise and Impact of Loneliness in Young People

The Effect of Increased Cortisol Levels on Learning

Addressing the Problem: Acoustics

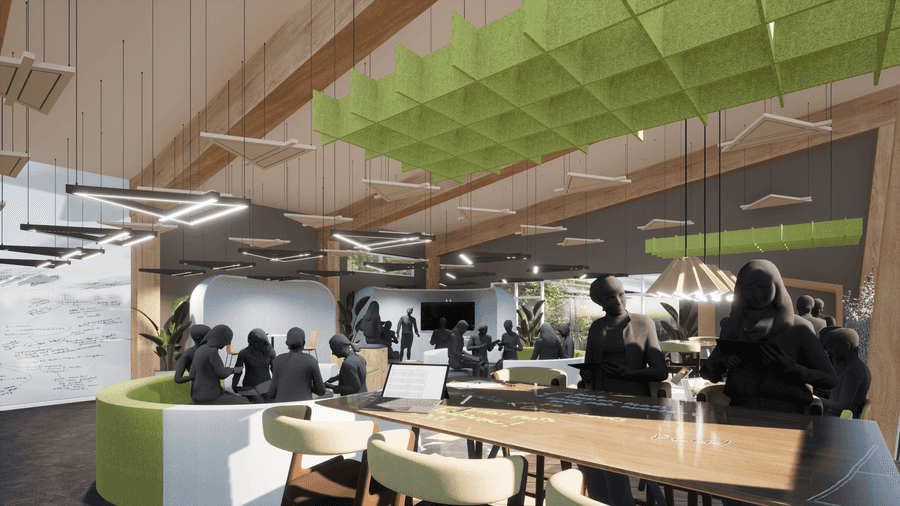

It’s clear that increased cortisol and feelings of isolation go hand-in-hand, acting as a slippery slope that can lead to myriad problems. In a lot of cases, young people are products of their environment. They are adept at absorbing information. Therefore, an enriching and stimulating environment fosters healthy growth and brain development [11]. Research has shown that school practitioners should prioritise enhancing their surrounding environment, as this promotes adolescent mental health and improves academic results [12].

This leads us to the matter of acoustics. Acoustics refers to the way in which sound waves interact with the space around them. When this interaction results in an unpleasant auditory experience, such as echoing or reverberation, the area likely has poor acoustics. Why is this significant? Research has shown that, when optimised, the acoustics of educational spaces can support learning and promote collaboration [13].

Collaboration is integral in combating feelings of isolation as it can identify problems, address needs, and hone social skills [14]. If students are in a space conducive to collaboration, reinforced by optimal acoustics, they will feel a sense of togetherness.

Exploring the Advantages of Improved Acoustics

Acoustics in a school environment is a constant that we cannot ignore. Whether students are walking through corridors, filing into an assembly hall, or collaborating in a classroom, they will feel the effect of acoustics. Therefore, every school should view acoustics as a ubiquitous presence that requires enhancement. How can this be done? Firstly, we must observe what factors can cause poor acoustics before considering ways to improve them.

As we’ve touched upon, echoing or reverberation are tell-tale signs of poor acoustics. Hard surfaces are one of the most common sources of echo. When a sound wave comes into contact with a rigid material, it reflects into the room, making it challenging to hear correctly. This stunts collaboration and may contribute to further feelings of detachment in students. Therefore, it’s important to note bare floors, empty walls, wooden or metal furniture, and uncovered windows [15].

When a room lacks materials that diffuse or absorb sound, acoustical issues arise. Soft materials reduce sound reflection and echo. This could be in the shape of cushioned furniture, fabric curtains, and foam panels. Even paintings hanging on the wall can help. Essentially, the best way to stop sound waves from bouncing around the room is to introduce objects that can absorb them on impact. [16]

The Impact of Acoustics on Behaviour

While we’ve covered the impact stress can have on young people concerning their development, it’s essential to view this from an acoustical sense. Our surrounding environment is a constant source of stimuli. Either positively or negatively, our brains are equipped to respond to such stimuli.

For example, noise triggers a stress response in the amygdala, a region of the brainstem that learns, over time, what sounds may signal impending danger [17]. Poor acoustics cause the amygdala to trigger a release of cortisol and an involuntary startled reaction. As mentioned before, increased cortisol levels impact not only mental health and behaviour but academic performance, too [9].

The Potential of Sound

Sound is powerful. Physiologically, as our body is over 60% water, we become an ideal vessel for sound to travel through. Therefore, it’s not surprising that sound has such an impact on us. As hearing is our primary warning sense, sudden or unfavourable sounds affect our bodies in various ways. It can increase our heart rate, change our breathing, and send our body into a fight-or-flight response [18].

In fact, a survey undertaken by the Remark Group and leading environmental psychologist Dr. Nigel Oseland revealed that 65% of workers say noise impacts their ability to complete work in an accurate or timely manner. Even more, 58% of people said that noise significantly affects their stress levels in the workplace [19]. Such results lend to the importance of improved acoustics in a school environment.

Increased Stress and Antisocial Behaviour

The impact of poor acoustical design extends beyond mere noise, as it can significantly disrupt the learning process, impede speech perception, compromise student behaviour, and ultimately hinder educational outcomes [20]. This can also feed into antisocial behaviour. When a space doesn’t accommodate sound well, it can be highly frustrating for students, as it may lead to further stress through miscommunications [21]. As young people find themselves in a vulnerable position due to their developing brains, further stressors are considered a key mechanism involved in persistent antisocial behaviour [22].

McBurnett and colleagues asked 335 young boys to think of and then speak about the worst thing that ever happened to them. Boys with the most extreme conduct problems showed increased cortisol response when recalling this event [23]. Another study found that when highly-stressed children experienced high spikes of cortisol in response to conflict, they were more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour, such as delinquency and running away from home [24]. Ultimately, if young people are exposed to stressors – such as environments with poor acoustics – they’re more likely to experience higher cortisol levels, leading to antisocial behaviours.

Poor Acoustics and Vulnerable Children

Improved acoustics doesn’t just help those prone to conduct problems. Children, especially those with hearing or learning disabilities, are deprived of a clear communication channel due to inferior classroom acoustics. A lack of communication acts as a barrier to learning, inhibiting intellectual growth, lowering self-esteem, and diminishing opportunities for vulnerable children to grow into their full potential [25].

As children haven’t fully developed their language skills, they need every opportunity to acquire vocabulary, learn to focus, and follow directions. Many children, particularly younger students, don’t have the capacity to draw from previous knowledge and fill in the gaps. Research shows that young students (without hearing or learning disabilities) would recognise only 66% of the words being spoken by the teacher [26]. Poor acoustics, therefore, acts as a severe barrier for all students.

What Can Be Done?

The question remains: how can schools make the most of improved acoustics? Planners must consider that addressing the issues sooner rather than later is much simpler and less expensive. With effective planning, administrators can address the issue of noise control and acoustical acceptability. For example, art rooms, music rooms, and gymnasia should be separated from the ‘quiet rooms,’ where work takes place. Heating, ventilation, or air conditioning system should be distanced from learning spaces, while many rooms will require absorbent material placed high on the walls [27].

Larger rooms, such as assembly halls, would benefit from an angled reflective panel over the speaking area so that the teacher’s voice projects clearly. Even things such as bookcases and corkboards can help absorb sound reflections. An effective acoustical engineer can recommend appropriate additions designed to reduce noise, such as proper carpeting and sound-absorbing shades or curtains. With the right support and preparation, any administrator can transform their school into an acoustically-sound environment.

The Impact of Clutter

Mess means stress. Research suggests that the state of our physical environment can affect our productivity, triggering coping and avoidance strategies [17]. Essentially, disorganisation and clutter have a cumulative impact on our brains. The visual distraction of clutter increases cognitive overload and can reduce our working memory. As such, when a learning environment is untidy and without order, students will experience the effects. Clutter can cause us to feel stressed, anxious, and depressed. For example, a recent study found levels of the stress hormone cortisol to be higher in mothers in cluttered home environments [18].

Additionally, in 2011, neuroscience researchers using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) and other physiological measurements found clearing clutter resulted in improved focus and increased productivity [19]. If a student feels unproductive in their learning environment, they’re more likely to experience spiked cortisol levels and feelings of inadequacy [20]. Emotions play a crucial role in how and why students learn. The design of their surroundings should represent this.

Improved Acoustics: Alleviating Loneliness

So, we find ourselves back at the fundamental issue of improved acoustics: helping young people develop into well-rounded individuals. Loneliness is a serious issue that’s only on the rise. Stressors, such as stunted communication and subpar learning environments, can lead to significant problems, including antisocial behaviour and a sense of detachment. Schools exist to support and guide students, to act as a sanctuary where they can grow into their full potential. Enhancing acoustics is an avenue leading away from isolation, allowing students to regulate their emotions and experience the sense of connectedness they deserve.

References

[1] – Nayanah Siva, August, 2020Loneliness in children and young people in the UK

[2] – Boxe, A. (2020). The Teen Brain, in Flux, Vulnerable to Mental Health Disorders. [online] www.brainfacts.org.

[3] – Stevens, J.S. et al. (2021) “Brain-Based Biotypes of Psychiatric Vulnerability in the Acute Aftermath of Trauma,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(11), pp. 1037–1049.

[4] – Lewis, K.R. (2022) “Teen brains aged faster than normal from pandemic stress, study says,” Washington Post, 1 December.

[5] – Won, C. (no date) ICYMI: Teenagers’ Brains Physically Aged Three Years After 10 Months of Lockdown During the Pandemic.

[6] – Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

[7] – Child mental health: recognising and responding to issues | NSPCC Learning.

[8] – Thau, L., Gandhi, J. and Sharma, S. (2019). Physiology, Cortisol. [online] National Library of Medicine.

[9] – Lmunoz (2015) Stress Hormone Hinders Memory Recall – Cognitive Neuroscience Society.

[10] – Terada, Y. (2018) “The Science Behind Student Stress,” Edutopia [Preprint].

[11] – Enriched Environments as a Potential Treatment for Developmental Disorders: A Critical Assessment

[12] – Aldridge, J.M. and McChesney, K. (2018). The Relationships between School Climate and Adolescent Mental Health and wellbeing: a Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Educational Research, [online] 88, pp.121–145.

[13] – Acoustics and new learning environment—a case study.

[14] – Gillies, R.M. (2003) “Structuring co-operative learning experiences in primary school,” ResearchGate [Preprint].

[15,16] – WebFX (2022) The Effects of Poor Acoustics – Illuminated Integration.

[17] – Intern, H. (2022) “Does noise stress you out? — Hearing Health Foundation,” Hearing Health Foundation [Preprint].

[18] – The 4 ways sound affects us – Julian Treasure.

[19] – Admin and Admin (2020) “‘Noise and Wellbeing at Work’ Survey, 2019 | Remark Group,” Remark Group [Preprint].

[20] – American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (no date b) Classroom Acoustics.

[21] – WebFX (2022b) The Effects of Poor Acoustics – Illuminated Integration.

[22] – Susman, E.J. (2006) “Psychobiology of persistent antisocial behavior: Stress, early vulnerabilities and the attenuation hypothesis,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(3), pp. 376–389.

[23] Aas, M. et al. (2020) “Childhood Trauma Is Nominally Associated With Elevated Cortisol Metabolism in Severe Mental Disorder,” Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11.

[24] Kobak, R., Zajac, K. and Levine, S. (2009) “Cortisol and antisocial behavior in early adolescence: The role of gender in an economically disadvantaged sample,” Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), pp. 579–591.

[25] – Singer, Miriam J. (2003) Acoustics in Schools.

[26] – Revisiting speech interference in classrooms (2001).

[27] – Singer, Miriam J. (2003) Acoustics in Schools.

Leave a Reply