Why School Connectedness Matters: The Impact on Students’ Emotional Well-being

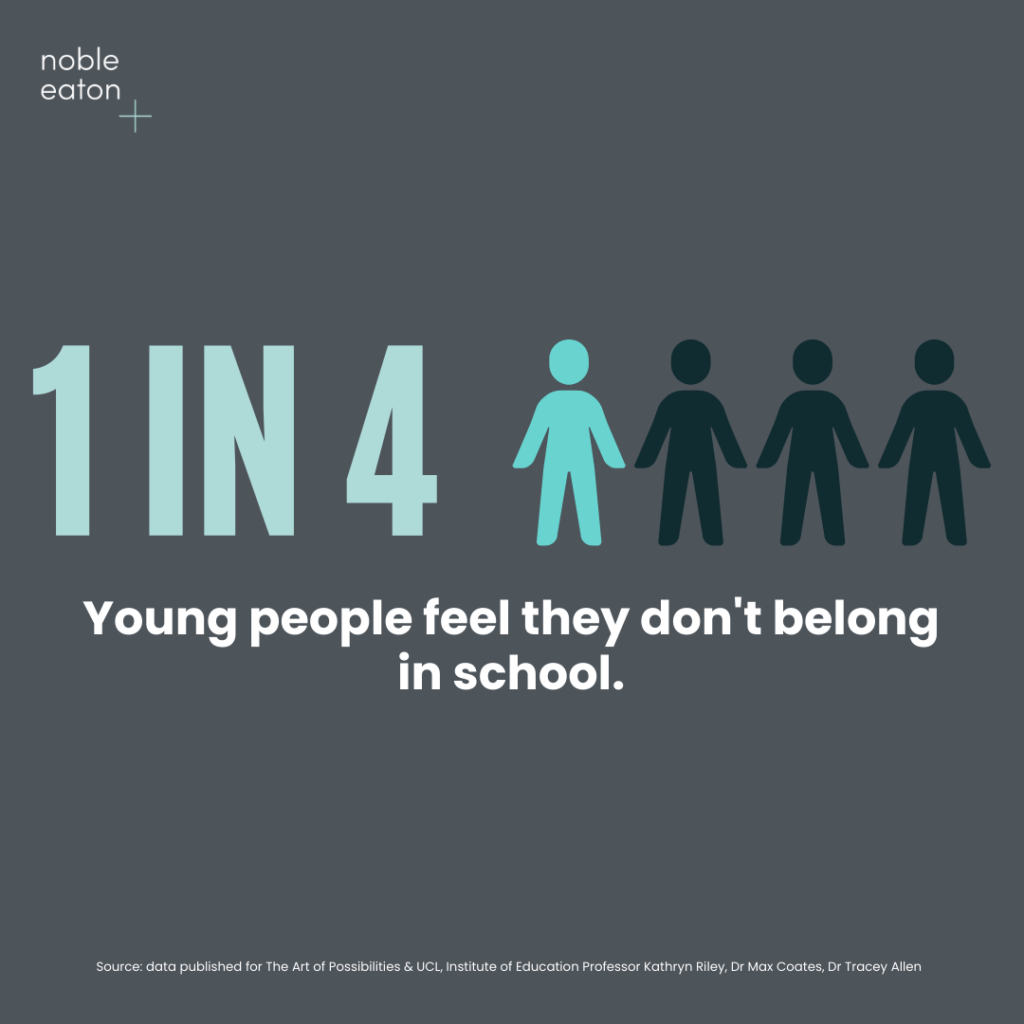

1 in 4 young people feel they don’t belong in school: a figure that appears to be rising. Research shows this sense of detachment has consequences for the mental health of your students. It’s causing ruptures in their behaviours and attitudes towards school and themselves. Let’s understand the critical role connectedness plays so that you can further support your student’s mental well-being.

What is school connectedness?

Let’s start from the beginning: school connectedness. What do we mean by this, exactly? School connectedness refers to the perception of students that their peers and educators in the educational institution have a genuine interest in their personal development and academic progress (CDC, 2009). Students are more likely to take on healthy behaviours and strive for academic success when feeling connected to their learning environment. The greater a student’s sense of detachment, the more likely they’ll feel they don’t belong (Berndt and Keefe 1995; Cauce 1986; Wentzel et al. 2004).

Why is school connectedness important?

In line with this thinking, The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health observed the impact of protective factors on the health and mental well-being of over 12,000 students between 7th and 12th grade (Blum et al., 2002). Interestingly, school connectedness is the most prominent protective factor in decreasing substance use, truancy, violence, and the risk of unintentional injury. In this study, the only aspect of school connectedness that fell behind family connectedness was its impact. Such a pivotal factor holds tremendous weight across student’s life.

When unravelling this thought further, we’ll nod towards Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs [1]. Here, the sense of belonging plays a vital role in motivating human behaviour. Maslow was adamant that companionship and acceptance sprung from a true feeling of belonging, bolstering links with family, friends, and other relationships. Williams and Page (1989) developed an instrument which measured the three central needs in Maslow’s hierarchy (safety, love and belongingness and self esteem) and reported that gratification of those needs aligned negatively with depression and neuroticism.

So, why is this significant? A strong argument presents itself here, recognising that emotions ‘have a significant impact on health and personal effectiveness’, as Spielberger, Reheiser & Unger outline (1995). When the emotional climate entwines the environment, connectedness follows. The instructional and organisational elements of the school environment have been well studied, including an educator’s ability to promote higher-order thinking (Zohar & Dori, 2003), link and integrate previous knowledge into instruction (Vermette et al., 2001), and establish clear parameters for classroom behaviour (Emmer & Stough, 2001). Ultimately, learning environments are bound to emotional development and are supplemented by a sense of belonging.

Emotional regulation: fostering a sense of belonging.

Mental health issues in young people are rising. Evidence suggests that an increase in the rate of conduct problems amongst students aged 15-16 steadily revealed itself amongst three birth cohorts in the UK (1958, 1970, and 1983-84) [2]. Even closer on the timeline, individuals’ feelings of sadness and hopelessness increased by nearly 40% in the ten years leading up to the pandemic, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System. One common link here? A sense of belonging.

Failing to find our place or establish a sense of community can lead to feelings of rejection and alienation. From an evolutionary standpoint, it’s natural for our brains to fear being cast from the tribe, leaving us to fend for ourselves. In support of this, one study found that we experience this feeling of social exclusion in the same region of our brain where we experience physical pain [3]. So, naturally, students are more likely to engage in healthy behaviours and succeed academically if they feel inherently connected to their school community.

According to Mayo Clinic, a sense of belonging aligns with connectedness. As such, students will feel less alone, have higher self-worth, and be able to cope more effectively with challenging life events [4]. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, research has shown that young people who feel connected to their school are less likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as drug use, alcohol and tobacco, and violence and gang involvement [3]. Hence why harnessing the power of school connectedness should be prioritised. With a healthy, supportive environment comes healthy, supported students.

Intrinsic motivation leads to empowerment.

If you were to ask an educator what they believe is the most important factor that contributes to a student’s success, they would most likely furrow their brow and narrow their eyes in thought. After all, it’s impossible to boil such an all-encompassing question down to one single aspect. However, intrinsic motivation is likely high up on any effective teacher’s list of priorities. And fortunately, intrinsic motivation is something that can be nurtured within a supportive environment.

The concept of school connectedness coincides with the principle of Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory [5]. They brought forward the idea that people are motivated to grow and change through the fulfilment of three psychological needs: competence, connection, and autonomy. When fulfilling their sense of belonging and attachment to others, their sense of self is reinforced. This leads to strengthened autonomy. Once a cohesive sense of self has been achieved, motivation will follow. Put figuratively, an intrinsic engine can effectively be charged by communal belonging.

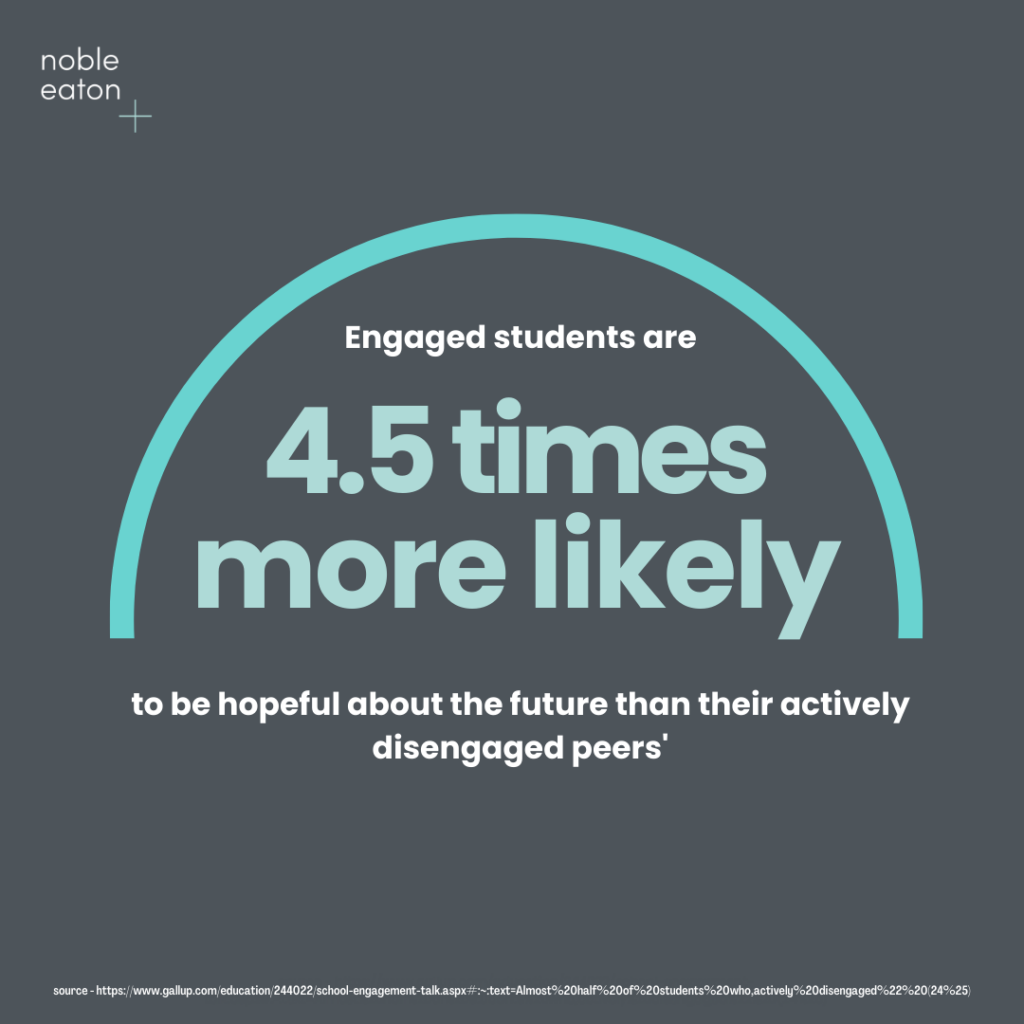

This can be supported by a study that found ‘engaged students are 4.5 times more likely to be hopeful about the future than their actively disengaged peers’ [6]. Once a sense of belonging has been established, young students are more likely to find themselves intrinsically motivated to succeed through improved engagement. Cognitive performance is also a pivotal player, as indicated by a study across OECD countries, revealing that improved reading performance has a strong connection with a sense of belonging [7].

Increasing self-worth and reducing loneliness

Amid rising expectations, both socially and academically, it’s common for a student’s feeling of self-worth to be tested. While young people can be equipped with the tools to foster intrinsic motivation, self-worth may be a challenge. It’s important to address this. A sense of belonging can be crucial in establishing self-worth, which in turn reduces the likelihood of mental health disorders such as depression or anxiety. In fact, research suggests that a coherent sense of identity may be associated with a person’s self-esteem and sense of purpose [8].

As such, school connectedness should be prioritised. Why? Because those with low self-esteem may fixate on their perceived ‘weaknesses’ or mistakes, causing their positive qualities to be internally shrouded. One study found that students who reported low self-worth had twice the odds of exhibiting anxiety symptoms [9]. However, if a student’s positive qualities were unshrouded by a close, connected community, their emotional well-being would reap the rewards.

How a lack of connectedness negatively impacts mental health

It’s time to recognise the other side of the coin. Whilst we’ve explored how connectedness can enrich students’ lives, what happens when connectedness becomes neglected? We’re social creatures. While some may protest, it’s generally natural for us to crave social interaction, to feel validated and accepted amongst our peers and authority figures. Therefore, a lack of school connectedness can have a lasting effect on a student’s mental health. Again, as we’ve briefly touched upon, Mayo Clinic has observed that anxiety and depression are mental disorders commonly associated with a subsided sense of belonging.

In 2022, 5.2% of children aged 11 to 16 said they often or always felt lonely, and 12.6% of young people aged 17 to 22 reported often or always feeling lonely [4]. It’s clear that depression and anxiety can deteriorate feelings of self-worth and instil a sense of loneliness. As this is already a considerable hurdle to leap over by itself, a lack of connectedness can only act as a catalyst. Now more than ever, students require complex support that cultivates their identity. If they feel unsupported and detached, these feelings may prove overwhelming. Schools are the ideal place to address this due to as they offer communal support.

How to encourage school connectedness

Simply attending school is not a considerable problem for most students. From day one of their academic journey, with encouragement from home, children can uphold consistent attendance. However, some students hold more risk of habitual absenteeism, leading to feelings of alienation and detachment. As young individuals uncover and realise their own character and abilities, they require support. The key word here is ‘individuals’, as every child has their own preferred way of learning and social assimilation [11]. If this style isn’t supported, they’ll be more likely to pull themselves away from the school environment.

Therefore, it’s crucial for schools to adapt to the needs of all students. Granted, this will be different for every school. Some may require secure communication and partnership between home and school, offering breakfast clubs or activities that allow a more prominent sense of belonging outside of learning hours. Others may benefit from altering the layout of their schools to facilitate a wider range of learning styles. Furthermore, creating spaces that allow for ease of collaborations with peers in both an academic and socialisation environment. Communal events such as school trips should be celebrated, and opportunities for extracurricular activities must be encouraged [12]. After all, a learning environment that fosters positive attitudes through adaptive, inclusive techniques will help instil life-long attitudes that stave off feelings of detachment.

How to make it happen

Arguably, school connectedness and emotional well-being have a synergistic relationship. Attunement towards your mental health allows for greater acceptance towards connectedness: greater connectedness allows mental health to thrive. Human-centric and solution-orientated designs embrace said relationship, offering increased support for your student’s mental health, cognition and learning outcomes.

The concept of connectedness can be at the forefront of your learning environment designs. A great place to start is making anxiety-reducing and inclusive spaces to motivate collaboration and, in turn, foster a sense of belonging. For instance, choosing polymorphic designs and the inclusion of biophilia in social areas helps to support ownership of learning in a low-anxiety, socially regenerative environment.

Granted, you want to improve your student’s emotional well-being to the best of your ability, and shining the light of school connectedness can make this happen. By booking a consultation with Noble and Eaton, you can discover the best design elements for your school and turn your vision into reality. Let’s make it happen!

References

[1] MSEd, K.C. (2022) “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Verywell Mind [Preprint].

School Connectedness Helps Students Thrive (no date).

Blum, R. and Nelson-Mmari, K. (2004) “The health of young people in a global context,” Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(5), pp. 402–418.

Williams, D., & Page, M. (1989). A Multi-dimensional measure of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Journal of Research in Personality, 23, 192-213.

Spielberger, C., Ritterband, L., Sydeman, S., Reheiser, E., & Unger, K. (1995). Assessment of Emotional States and Personality Traits: Measuring Psychological Vital Signs. In J.N. Butcher (Ed.) Clinical Personality Assessment: Practical Approaches (pp.35-58). New York: Oxford press.

Zohar, A., & Dori, Y. (2003). Higher order thinking skills and low achieving students: Are they mutually exclusive? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 12, 1

I. (2016) “EMMER AND STOUGH CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT Classroom Management: A Critical Part of Educational Psychology, With Implications for Teacher Education,” www.academia.edu [Preprint]

[2] Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge

[3] MacDonald, G. and Leary, M.R. (2005) “Why Does Social Exclusion Hurt? The Relationship Between Social and Physical Pain.,” Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), pp. 202–223.

[4] LCSW, A.T. (2022) “Is having a sense of belonging important?,” Mayo Clinic Health System [Preprint].

[5] Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2015) “Self-Determination Theory,” in Elsevier eBooks, pp. 486–491.

[6] Hodges, B.T. (2023) “School Engagement Is More Than Just Talk,” Gallup.com, 30 March.

[8] Stets, J.E. and Burke, P. (2014) “Self-Esteem and Identities,” Sociological Perspectives, 57(4), pp. 409–433.

[9] Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study

[10] Pikulski, P.J. (no date) School Connectedness and Child Anxiety.

Jackw (2021) “Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, pioneering psychologist and ‘father of flow,’ 1934–2021,” University of Chicago News, 1 November.

[11] The Importance of Learning Styles in Education

[12] Stets, J.E. and Burke, P. (2014b) “Self-Esteem and Identities,” Sociological Perspectives, 57(4), pp. 409–433.

Leave a Reply